How did we get here? Simply put, bad government—from outdated zoning laws to a 40-year-old tax provision that benefits long-time homeowners at the expense of everyone else—has created a severe shortage of houses. While decades in the making, California’s slow-moving disaster has reached a critical point for state officials, businesses and the millions who are straining to live there.

This fall, as President Donald Trump blamed Democrats for the situation on his swing through the state to raise money for his reelection, lawmakers in Sacramento passed some of the most sweeping legislation in years to address housing affordability. Google, Facebook Inc. and Apple Inc. are throwing billions of dollars at the issue. But nobody’s kidding themselves that it’s enough.

“Broadly speaking, there is no solution to the California housing crisis without the construction of millions of new houses,” said David Garcia, policy director for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley.

McKinsey & Co. estimated in 2016 that California needed some 3.5 million more homes by the middle of next decade—a figure that Governor Gavin Newsom made a central part of his administration’s goals. A more recent analysis suggests it may take the state until 2050 to meet the target.

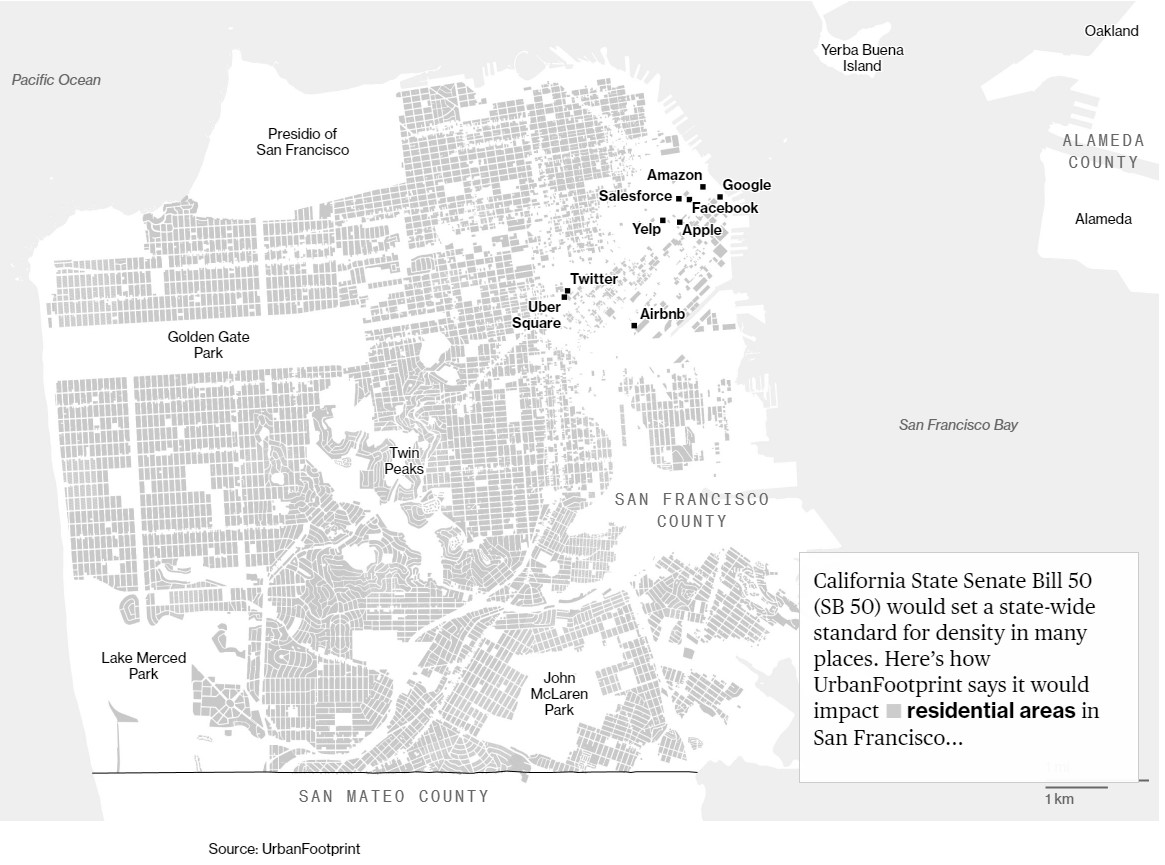

As severe as this sounds, the rest of the country is becoming more—not less—like California. During the longest economic expansion on record, the U.S. has been building far fewer houses than it usually does, pushing prices further out of reach for a vast portion of the population that has barely seen incomes rise.

“California is not alone,” said Chris Herbert, the managing director of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. “It’s just more extreme.”

Housing Costs by State

For the poorest Americans, affording adequate housing has long been a challenge. But in California, it’s become a middle-class problem, too.

Silicon Valley teachers are having such a tough time affording rents that Facebook just announced a $25 million donation to build subsidized apartments for them. Another Bay Area town recently decided to retrofit an old firehouse into barracks for its cops after they took to sleeping in their cars.

In a state where more than 40% of residents are considered cost burdened for housing—paying more than 30% of their income toward shelter—even people in high income brackets are often stretching their budgets.

California Cost Burdens Hit All Income Brackets

- California metro areas

- Metro areas in other states

- U.S. Average

Local jurisdictions in California hold enormous sway over what gets built. Officials have often caved to NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) pressure against new development, much of it in the name of protecting the environment or preserving “neighborhood character.”

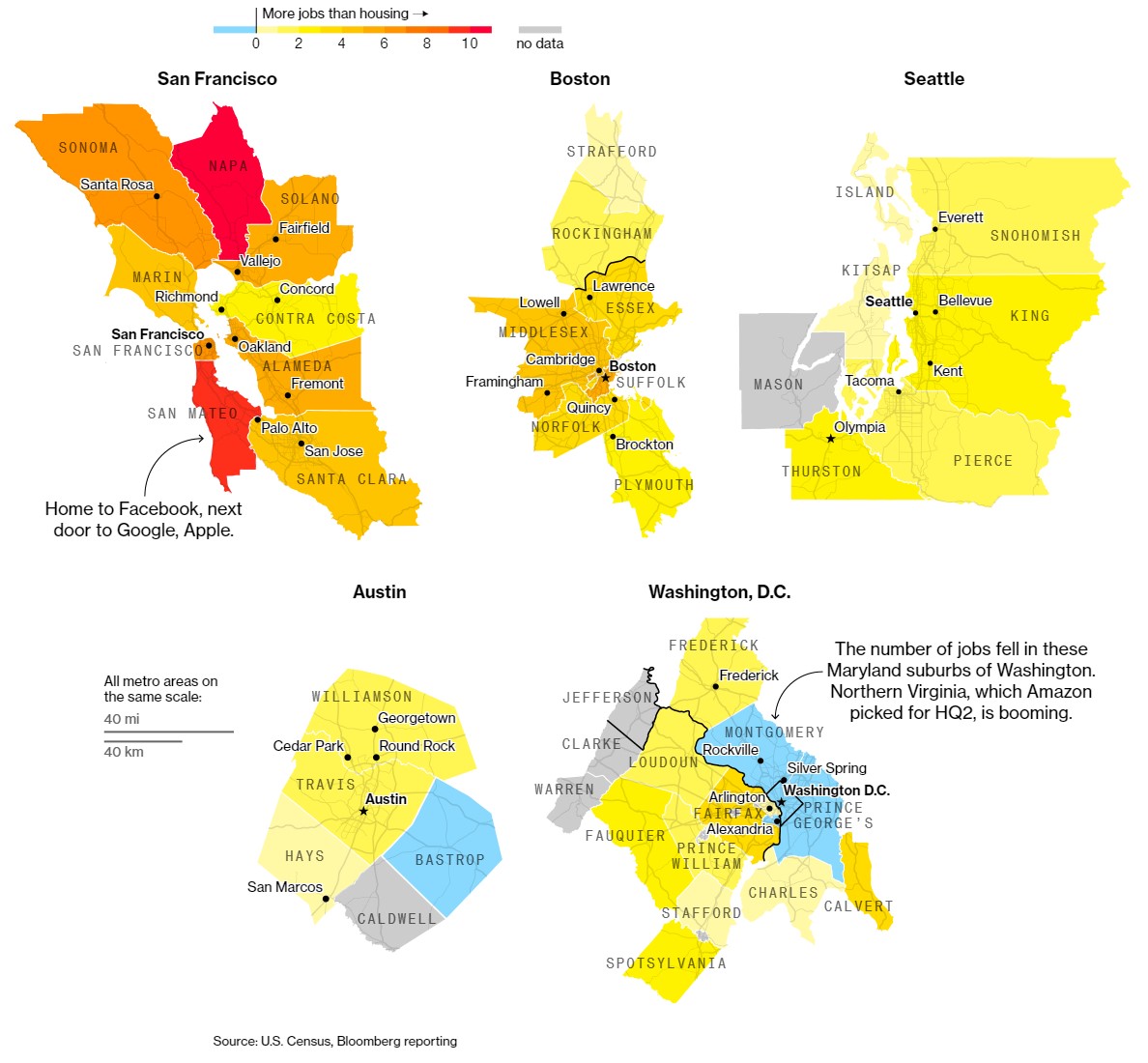

Parts of the state were downzoned starting in the 1970s, making it harder to build dense urban areas and contributing to racial segregation and sprawl. Three-quarters of the residential land in Los Angeles is restricted to single-family homes, according to UrbanFootprint, software that helps government and businesses understand cities and urban markets. In San Jose, the figure is 94%.

Housing Permits Per Capita

California also has a distinct burden: Proposition 13, a measure approved by voters in 1978 that limits property-tax increases on homes until they’re sold. That’s been a boon for Baby Boomers who’ve lived in their houses for decades and aren’t assessed at anything close to their property’s market value. But it’s especially unfair to their children, who are in effect subsidizing their parents’ generation.

Prop 13 also created a fiscal incentive for many cities to favor new commercial development over residential construction—and heap fees on developers to fund budget gaps.

For decades, many Californians have just moved farther out of town to find cheaper places to live. But as climate change increases the intensity and frequency of wildfires—leading to devastation and billions of dollars in costs—officials may decide to put some areas off-limits for new construction.

That could exacerbate the housing shortage, said Stephen Levy, director of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy in Palo Alto. “At some point, the regions that are under pressure to build more housing are going to find areas that are prone to more frequent fires,” he said.

Not surprisingly, some residents aren’t waiting around to see what happens. In recent years, younger, less-educated and lower-income folks have led the exodus from the state, according to an analysis by the Legislative Analyst’s Office. They’re being replaced by high earners with graduate degrees in what amounts to a sort of state-wide gentrification.

Corporations are also decamping for lower-cost locales. Even companies like Apple, Facebook and Google that are still adding employees in the region have looked to cities including Atlanta, Austin and Pittsburgh for growth. The three tech giants have also pledged to address the issue itself, with a total of $4.5 billion in commitments toward affordable housing development in the state.

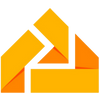

Those very same companies have been blamed for contributing to the crisis by bringing in a flood of workers over the past decade while housing supply failed to keep up. The Bay Area saw 5.4 new jobs for every unit of housing it built between 2011 and 2017.

Bay Area Housing Supply Failed to Keep Up With Its Job Growth

What now? Newsom has vowed to be aggressive, and has taken steps such as suing a city for refusing to build affordable housing. At a ceremony last month to sign an anti-rent-gouging law, he was blunt about what else needed to be done: “We need to put in more damn housing.”

The coming year is likely to bring a showdown over one of the biggest issues: land use. An ambitious bill to force cities to accept density around transit and job centers was tabled in May because of opposition from suburban legislators, generating an outcry. Its backer, state Senator Scott Wiener, has vowed to try again in 2020. Whether or not he’s successful, the bill demonstrates the kind of sweeping change that researchers say is necessary to build more homes where they’re needed most, without sprawling into risky areas.

Los Angeles neighborhoods that have seen prices soar because of an influx of tech-heavy jobs would potentially accommodate more growth.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. California can keep attracting all the “highly talented individuals that make the knowledge economy work,” said Herbert of Harvard’s Joint Center. But, at some point, he added, “the state’s economy will be strangled by the inability to have a broad workforce.”

In other words, a place known for diversity, innovation and quality of life may be left for no one but the rich and lucky, who got there before it was too late.